I loved my grandfather more than any human being on earth and I know that he felt the same way about me. His busy world stood still whenever we were together. I was his heart, his soul, his Dorothy; named for my grandmother who died from lung cancer a year before I was born. She was only forty-four years old.

At the end of the school year my mother dressed me in a smart navy-blue blazer with gold buttons and a pair of navy-blue gabardine slacks and sent me (and a suitcase filled with color coordinated Danskin outfits and Keds in every color known to man ) by myself on a plane to Las Vegas so I could spend the summer with my grandfather at his hotel. She would pull a gold Star of David from her jewelry box and fasten it around my neck to prevent the plane from crashing. Who knew that a Jewish star could keep a plane in the air? When the plane landed, the door opened and the desert heat socked me in the face, marking the beginning of my summer. My grandfather had VIP status and was able to drive his car onto the tarmac to pick me up when I reached the bottom of the stairs. His driver’s name was Red because he had red hair just like Red Skelton. Red had been working for my grandfather since the foundation was poured for the hotel.

“He’s loyal like a dumb dog,” my grandfather would say of him.

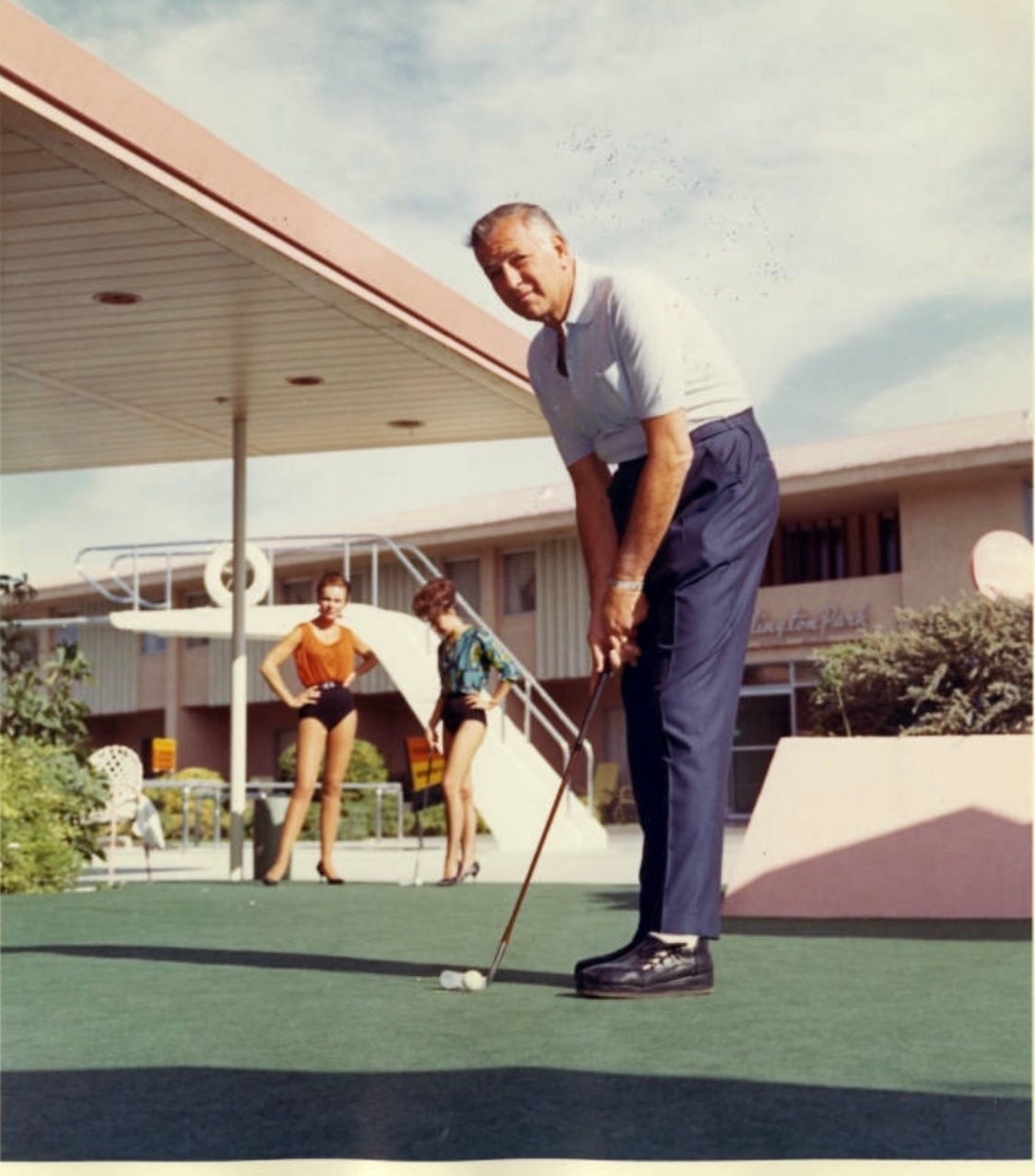

I would wake my grandpa at eleven each morning and bring him the small silver tray with a vial of insulin and a needle that his housekeeper Inge had prepared. At six feet six inches, he would swing his long limbs over the side of the bed, raise the leg of his pajama shorts and plunge the needle into his upper thigh. After his shot we headed for the dining room to eat a hearty breakfast of sunny side up eggs on butter-soaked toasted rye bread with a gargantuan pile of bacon on the side. My mom tended not make bacon in our house because it smelled up the upholstery. After he got into his work clothes, he took me to his office on the handlebars of his bicycle. The office was minutes away from his home which was in the back of The Sands. We rode on the well paved sidewalk of the interior courtyard of the hotel, winding our way around two pools and a putting green on the way. The only traffic we encountered was the occasional golf cart that carried food from room service to the guest rooms. The main part of the hotel was a tall mustard colored cylindrical tower. My grandfather loved to walk in through the back door of the kitchen so he could greet Siriacco the chef and his staff and sample the food before it was served to the guests. My grandfather never smoked or drank but boy could he eat. He’d always linger a bit too long around the exquisite creations of his pastry chefs.

“Not for you Mr. Entratter. Don’t worry, I made something specially for you. No sugar.”

“No fun.” He snorted.

He smiled as he pushed through the swinging double doors that led to the Copa Room. I felt my heart quicken as I never knew what I would find. On one of my visits in February, a young Quincy Jones sat at an empty table smoking cigarette after cigarette while he listened to Count Basie practice with the rhythm section of his orchestra.

“Frank’s gonna take his break on stage after “Summer Wind,” pour himself a scotch and tell a few stories. I want you to follow up his punchlines with a drum roll, a ba-da -bum, and a strike of the high hats.”

When the showgirls who were doing their costume fittings in the dressing room got wind that my grandfather was in the house, they would slither out to parade themselves in front of him. He had a reputation of being a real ladies’ man even though he was technically still married to Corrine, his second and third wife. Apparently, he had found Corrine in bed with another woman before he began divorce proceedings for the second time. I overheard my father weighing in on the situation when he found out.

“ You know how many guys would kill for an opportunity like that?”

“Mickey!” My mom pretended to be shocked in front of me.

“What do you care? You hate her guts anyway!” She didn’t argue with him there.I despised her as well.

By now my grandfather was completely surrounded by some of the most beautiful women on earth, wearing cheeky leotards with fishnet stockings and sky-high heels. For that brief moment, I ceased to exist. When he was done having his ego stroked, we walked through the casino where the maintenance men were vacuuming the rich red carpet and Tony Grasso, the pit boss, was inspecting the felt on the crap tables for tears. Tony always had a small yellow pencil behind one ear and a cigarette wedged behind the other. He styled his hair like a young Sal Mineo and had over-active sebaceous glands that made him look like he was always sweating. He was also a chain smoker who smoked each cigarette clear down to the filter.

“Tough night I hear.” My grandfather put his arm around Tony’s shoulder while they both spoke in hushed tones.

“Yeah, he got a little crazy, but hey, that’s Jerry. I tell ya, he’s fine when it’s just booze. But when he mixes the booze with other things, that’s when it all heads south.”

After receiving a brief update on what had transpired the night before, my grandfather and I took the elevator up to the suite where Jerry Lewis stayed. He rapped on the door with his cabochon star sapphire pinky ring. A few seconds later, a very large man who doubled as Jerry’s driver and body guard answered the door.

“Jerry’s getting a rub down.”

“That’s nice.” My grandfather pushed past him into the next room.

A tall muscular man dressed like Jack La Lane was giving Jerry a massage. Jerry was out cold on the table. He had dampened cotton pads on his eyes and an ice pack on his head.

“I’m just tryin’ to get his neck straightened out so he can do the show tonight, Mr. Entratter. That must have been some punch he took.”

My grandfather shook his head and turned to leave. He mumbled something under his breath that I don’t care to repeat.

We took the elevator to his office on the mezzanine where I would sit on the floor and build things with casino chips, and brightly colored plastic monkeys and dolphins that the bartender used as a garnish on my orange Julius’.

After an hour or so of work we would head to the pool to meet his buddies, Sammy Davis Jr. and Peter Lawford although Sammy and my grandfather were particularly close. My grandfather was a very active member of Temple Beth Shalom and was instrumental in Sammy’s conversion to Judaism.

The lifeguard gave me swimming lessons while the waitresses and cigarette girls wearing hot pants and high heels paraded in front of Sammy and my grandfather in his cabana. I was invisible again. I became friends with the kids whose parents worked in the hotel. For fun, we would fry eggs on the sidewalk or hold a magnifying glass over an ant hill and watch as they shriveled and sizzled. We found scorpions hiding under rocks in the cactus beds, trapped them under glass jars, and fried them under the magnifying glass as well. At the time Vegas was still mostly desert and life there was quite rugged in comparison to my life on Sutton Place. We had locust storms of biblical proportions and rattle snakes sunning themselves in rock gardens. Once we even had to tear a Gila monster off the muzzle of my grandpa’s yellow lab.

When the sun began to set, we would drive into the desert to Edna Grey’s horse ranch where my grandfather kept his Palomino ponies. Edna was a rugged cowgirl with leathery skin, wiry grey hair, and broken beige teeth. My horse was named Popcorn and my grandpas was of course named Sugar. My summer nights were glorious. The scorching dry air would give way to the cool desert evening as we rode past tumbleweeds, jack rabbits and old cement bomb shelters.

Later, I accompanied my grandfather to the casino where he would hoist me on to the edge of the crap tables and let me roll the dice. Afterwards, we rolled into the Copa Room to watch the first show of the evening where I would fall asleep in a banquette. I wasn’t bored. It was just that in those days entertainers took up residency at the hotels for two months at a time and there was only so many times I could watch the same show without falling asleep. My grandfather brought me back to his home and read me bedtime stories from the Old Testament. My favorite was the story of King Solomon threatening to split the baby in half to smoke out its true mother.

I went home kicking and screaming at the end of each summer and spent the first few weeks after my return in profound sadness. The contrast between the rarified world that my grandfather shared with me in Las Vegas every summer and my life at home in Manhattan was vast. To be clear, both worlds were marked by many blessings but I always felt that it was less about privilege and more about the deep emotional connection I felt with my grandfather. How was anything or anyone going to compare? At home I ate my breakfasts alone in the kitchen. My father left for work at the crack of dawn and my mother, who was not from the morning people, slept in. There was no butter-soaked toast or perfectly crisp rashers of bacon, just the boxes of Frankenberry or Count Chocula cereal that I picked out for myself the night before to save time( I preferred Frankenberry because it turned my milk pink).

I got on the school bus one morning thinking nothing of the fact that my mother was already up and out of the house. Our bus driver was named Osgood, but we called him Ozzie pickle nose because his nose was bulbous and red, and he always smelled of whisky. The kids who lived on the Sutton Place route loved him because he taught us Irish drinking songs like “I’ll tell me ma” and “Whisky in the Jar.”

“Pay attention to yer teachers and do yer work or the whole lot of yous will end up like me; driving little shits like you to and from school day in and day out,” he’d say with his gruff and somehow endearing way.

The day was uneventful and torture as usual. I was convinced that my homeroom teacher, Mrs. Cone, took nasty pills before coming to school each day. Normally this wouldn’t bother me because homeroom was only for the first twenty minutes of each day. Unfortunately, she taught my level of math, English and social studies, so I had her all day long five days a week. I think she hated me as much as I hated her. When I asked my parents if I could switch out of at least some of her classes, they refused.

“You’re not going to love everyone you deal with in life, but you need to learn how to make things work,” my mother would say. This was a tall order because I was being seriously bullied by an adult.

The fact that a drunken bus driver was the highlight of my academic day was a sad commentary indeed. Ozzie had the news on the radio on our way back from school. I usually sat quietly and listened because I wasn’t allowed to watch television on weekdays and the New York Times seemed like too much trouble to fold, much less read.

“Entertainment giant Jack Entratter of the famed Sands Hotel in Las Vegas died today. He was fifty-seven years old,” the newscaster said flatly.

This was so out of the realm of what I expected to hear at that moment that I sat for a minute to let the news of my grandfather’s passing sink in. Ozzie had no idea who my grandfather was, so he probably thought that I was crazy when I opened the door to the van and jumped out without warning. I ran home with my heart pulsing in my ears. I was met by my Aunt Carol who was my father’s sister.

“Please don’t upset your sister or your brother by telling them.”

“But how? How did he die? I don’t understand!”

“Your grandfather was riding his bicycle to work when he fell and hit his head on the sidewalk.”

“I don’t understand. I hit my head all the time.”

“It’s called a cerebral hemorrhage.”

I cried alone until my parents came home with my grandfather’s body from Las Vegas. His wish was to be buried next to his Dorothy. The funeral was the next day. My parent’s belief that children should not be exposed to death made zero sense to me because I had seen a photograph of a three-year-old John John Kennedy saluting his father’s casket as it passed. I didn’t argue because my mother looked so weak that upsetting her with one of my foot stomping, tearful meltdowns felt entirely inappropriate. If I couldn’t handle “No” then how could I be expected to handle a funeral.My mother covered all the mirrors in the house and replaced our living room furniture with wooden boxes for the shiva.

My grandfather was raised as an Orthodox Jew so the mournful prayers were in Hebrew and I couldn’t understand a word. The only thing I understood was that he was gone and that I would never hold his hand or hear his voice again. My favorite person in the entire world was dead. I was eleven years old but my heart aches to this day.

I knew the backstory but didn’t know your beloved Grandfather died so young from a bicycle accident. But those summers in Vegas shaped you as a person & another reason I hold you in such high regard. You are not impressed with wealth & station in life but the essence of a person.

To have loved, and been loved as you have with your grandfather is perhaps the greatest gift a person can receive in this life. How fortunate you have been!